The Education and Public Programs Team at the Nixon Library is pleased to remind you that the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) continues to be an excellent source for entertaining and historical content! Simply follow the links below for additional information.

![]()

Nixon and the Supreme Court

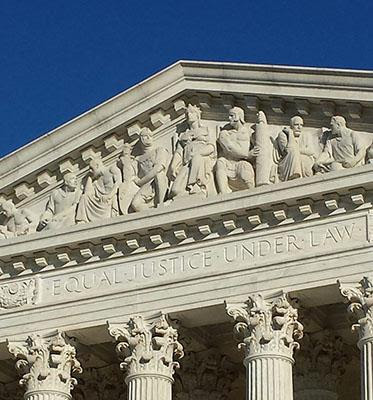

“West Pediment of the Supreme Court Building.” Photograph, Catherine Fitts, From Collection of the Supreme Court of the United States, January 28, 2021, https://www.supremecourt.gov/ (accessed September 15, 2021).

“Equal Justice Under Law is not merely a caption on the façade of the Supreme Court Building: it is perhaps the most inspiring ideal of our society. It is one of the ends for which our entire legal system exists...It is fundamental that Justice should be the same, in substance and availability, without regard to economic status.”

- Justice Lewis F. Powell, Jr., ABA Annual Meeting, August 10, 1976.

The first Supreme Court, established by President George Washington and the Congress of the United States, came into being on September 24, 1789. When it was initially assembled in 1790, the fundamental order of business was to organize the lesser court system and approve bar appointments. It wasn't until the Court's second year that the justices heard a case (West v. Barnes) and passed down a decision. September 24, 2021, celebrates 232 years of the Supreme Court. There have been seventeen chief justices and 103 associate justices confirmed to the Court since 1790; four of which were nominated and confirmed during President Richard Nixon's tenure. The Burger Court (headed by Chief Justice Warren Burger, a Nixon nominee) heard and wrote decisions on many of the cases in the news today.

![]()

A Brief Overview

The Charters of Freedom displayed in the National Archives Rotunda, Washington DC. National Archives and Records Administration Building. “Founding Documents in the Rotunda for the Charters of Freedom.” Photograph. National Archives Museum, https://museum.archives.gov/founding-documents. Accessed 6 July 2021.

Article III, Section One of the United States Constitution established the Supreme Court in theory, stating, "The judicial Power of the United States, shall be vested in one supreme Court." Still, it was the Judiciary Act of 1789 brought forth by Congress that created the Supreme Court. The size was initially capped at six justices (one chief justice with five associate justices) appointed by the President and confirmed by the Senate, but over the next eighty years, that number increased to a total of nine (one chief justice with eight associate justices) who hold office for life.

Article III, Section Two establishes the Court's jurisdiction, stating, "The judicial Power shall extend to all Cases, in Law and Equity, arising under this Constitution, the Laws of the United States, and Treaties made, or which shall be made, under their Authority..." This jurisdiction applies to any case that involves constitutional or federal law, both original and appellate. The Supreme Court is inherent to our constitutional form of government. The roles are defined best at uscourts.gov, stating,

![]()

Nixon’s Nominations

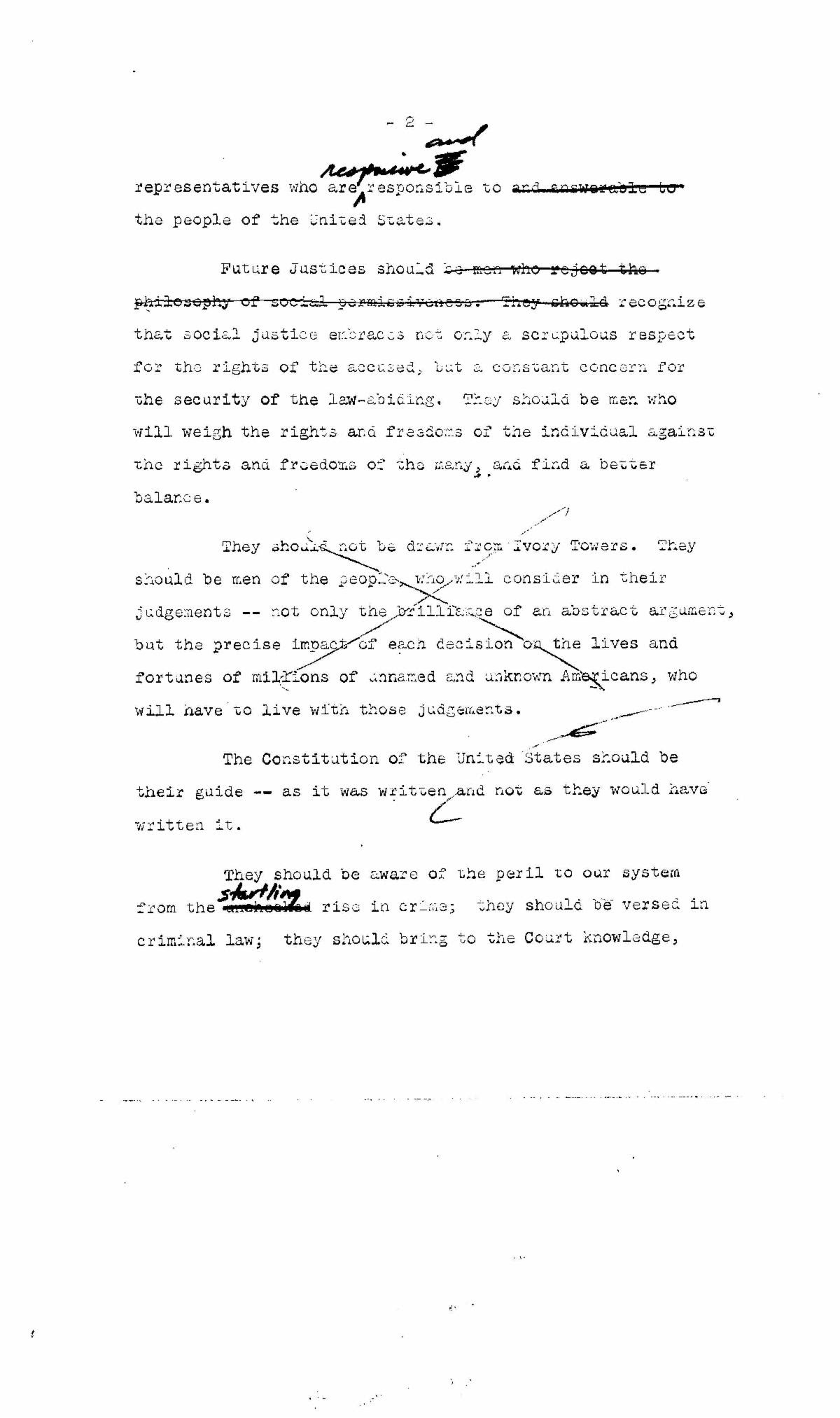

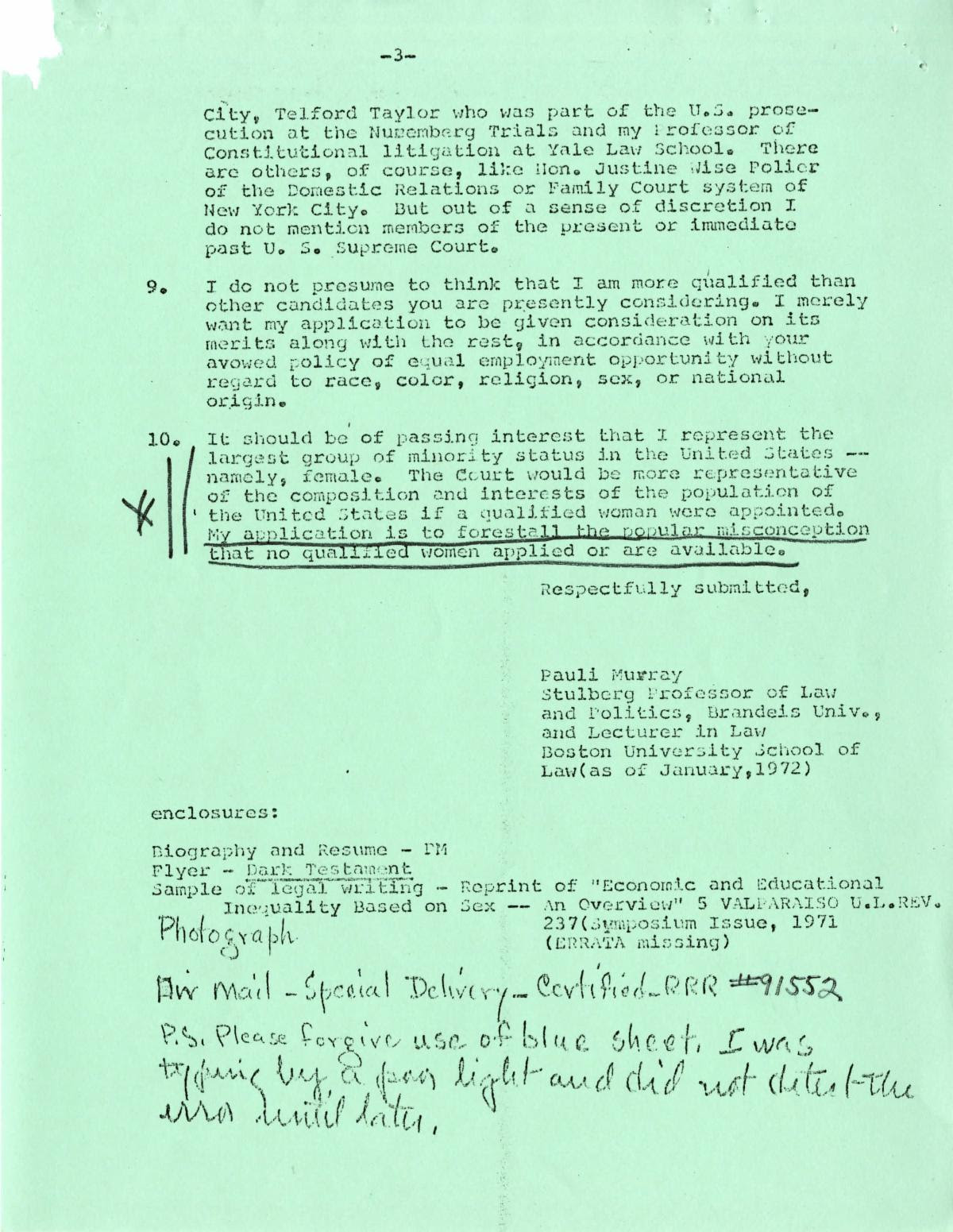

A rough draft of candidate Nixon’s speech regarding the Supreme Court vacancies. Richard Nixon Returned Materials: White House Special Files: Box 35, Folder 16; October 23, 1968. Richard Nixon Presidential Library and Museum, National Archives and Records Administration.

Richard Nixon nominated six justices to the Supreme Court (four of which were confirmed by the Senate) during his presidency. The confirmation of Chief Justice Warren Burger, in 1969, to replace outgoing Chief Justice Earl Warren fulfilled a campaign promise from the new President. As Nixon stated in the document above, he would appoint justices that “would be strict constructionists. They would see themselves as interpreting the law, not making the law. They would see themselves as caretakers of the Constitution and servants of the people, not super-legislators with a free hand to impose their political and social viewpoints upon the American system and the American People.” Since the Constitution does not define the exact powers and prerogatives of the Supreme Court, it is the Chief Justice and the associate justices’ job to interpret the law and determine how it is applied. Many Nixon voters hoped that Burger, a strict constructionist, would vacate some of the more controversial decisions that the broad constructionist Warren Court had made.

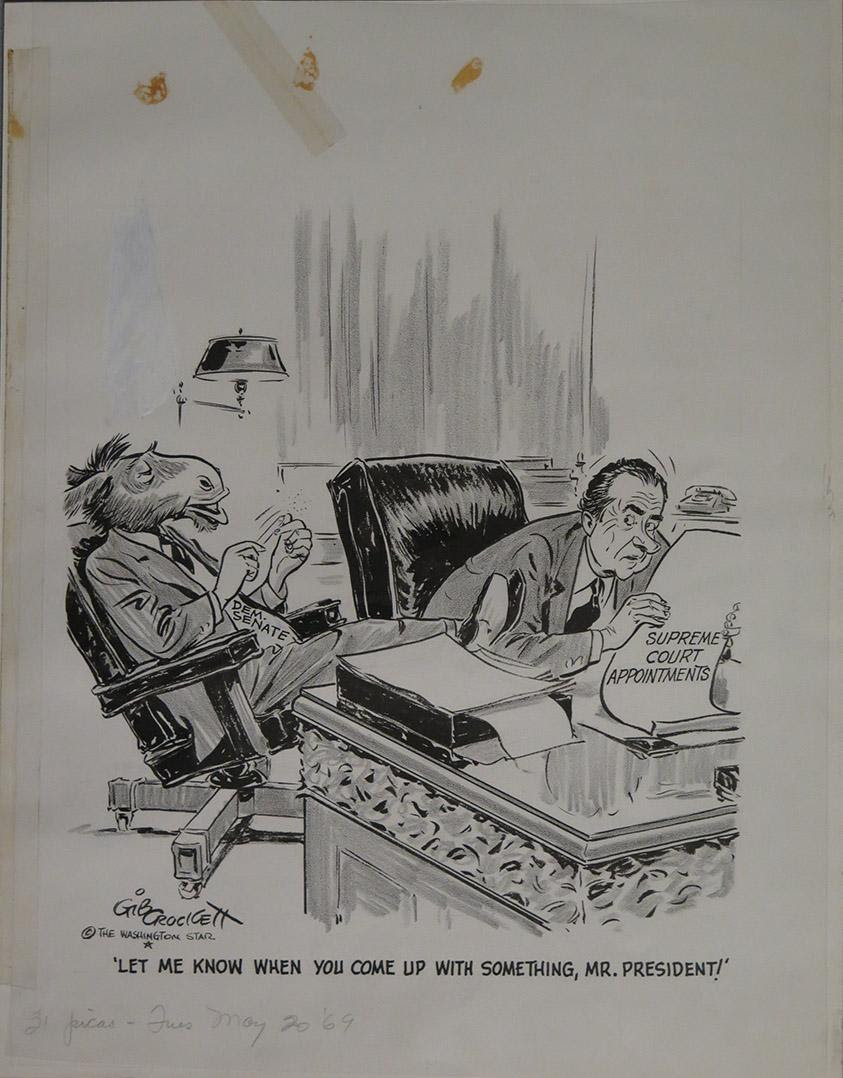

The openings also created an opportunity to nominate a woman to the Supreme Court. First Lady Pat Nixon, a strong supporter of the Equal Rights Amendment, lobbied for a female nomination, believing women were underrepresented in government. Women's activist/law professor Pauli Murray submitted a letter to President Nixon in 1971 asking for consideration for the position vacated by Justice Hugo L. Black.

Letter, Pauli Murray to President Nixon; White House Central Files: Alphabetical Name Files; Richard Nixon Presidential Library and Museum, Yorba Linda, California

After the Senate rejected two of his nominations (Clement Haynsworth and G. Harrold Carswell), the President considered California Court of Appeals Judge Mildred Lillie but changed course after the American Bar Association deemed her unqualified. A recorded conversation between President Nixon and his daughter Julie illustrates how disappointed the First Lady was when the President selected a man to fill the vacant position. The presidential nominations and subsequent confirmations of Harry A. Blackmun (1970), Lewis F. Powell, Jr. (1971), and William Rehnquist (1971) replacing liberal justices shifted the Court's ideological composition to the conservative, a position it maintains to this day.

An original cartoon from the newspaper The Washington Star. Gift of Gib Crockett to President Richard Nixon, D.1969.4162

Major Case Decisions

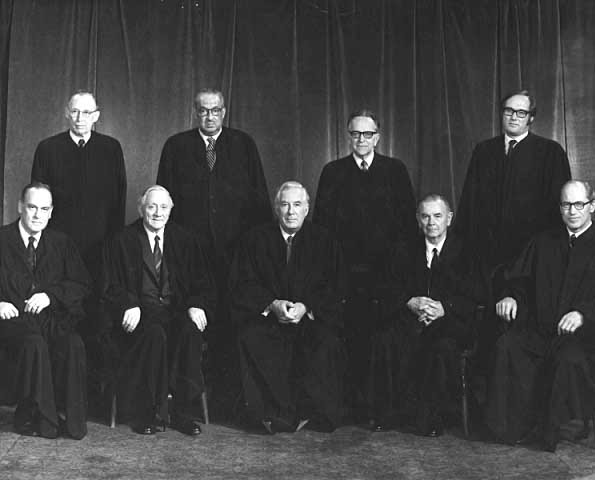

A photograph of the Burger Supreme Court. “United States Supreme Court.” Photograph. Minnesota Historical Society, http://collections.mnhs.org/cms/display.php?irn=10747202. Accessed September 20, 2021.

The 1970s were a time of significant change in the United States, with marginalized communities demanding equal rights under the law, environmental accountability, and questioning governmental power. The National Constitution Center has stated, “The ‘Burger Court’ dealt with everything from abortion to capital punishment to pornography, and it most likely ended Richard Nixon’s stay in the White House in 1974.” Many cases presided over by the Burger Court continue to make headlines today, including the six listed below.

North Carolina v. Alford (1970)

New York Times Company v The United States (1971)

The United States v. Nixon (1974)

September 24, 2021, marks the 232nd anniversary of the United States Supreme Court. During his presidency, Richard Nixon was instrumental in the rightward ideological shift of the Court with the appointments of Chief Justice Warren Burger and Associate Justices Blackmun, Powell, and Rehnquist. The Burger Court decided controversial cases that still headline the news nearly 50 years later, including, somewhat ironically, one against President Nixon himself regarding executive privilege with the Court's opinion, read by Chief Justice Burger.